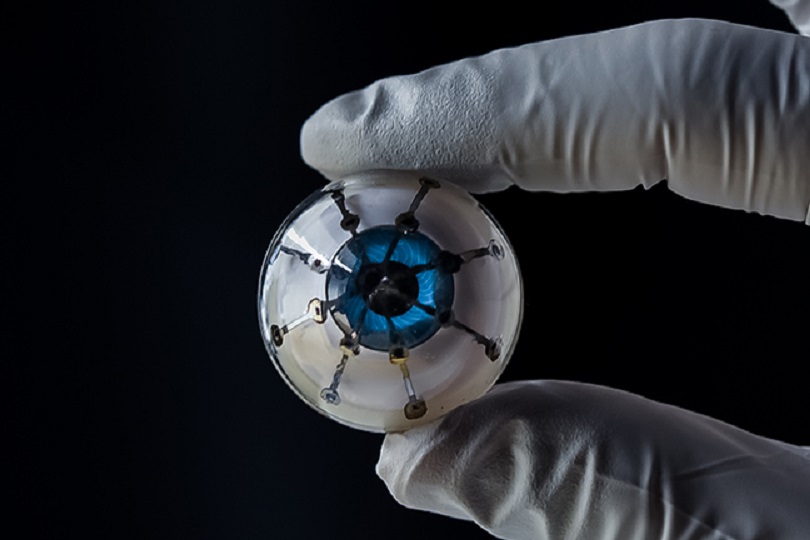

Bionic eye made by a printer

Researchers have managed to print photosensitive cells in a dish shape, laying the foundation for a bionic eye that could help the blind see again.

Although putting cells that convert light into electrical pulses in a small glass container doesn’t sound like a major advance, it has overcome an important hurdle: printing on a curved surface is often difficult, because the printed polymer ink does not remain in place. The polymer ink achieves an external quantum efficiency of 25%.The findings are described in the journal Advanced Materials.

Ears, organs and skin

The researchers at the University of Minnesota in the US already have some experience with printing body parts, having previously made ears, organs and bionic skin. However, an eye is much more complicated, as it concerns an intricate mechanism of photosensitive cells and electrical signals.

The printed eye is long from being as advanced as the human eye. It consists of a substrate of silver nanoparticles, which, unlike other materials, do not settle on the spherical glass surface. The substrate is covered by a layer of photosensitive polymers, which capture external light and convert it into electrical pulses. Printing takes about an hour.

Little light

The result is still rather limited – the 'eye' contains very few photosensitive polymers, which can only detect the presence of light, but are not sensitive to its intensity. Proof of concept is therefore a better description of this development. The researchers’ next objective is to place more receptors on a spherical substrate, and they also want to try to make it flexible so that it can be placed in an eye socket. That is the dream of lead researcher Michael McAlpine, whose mother is blind in one eye.

However, even if the researchers successfully manage to do all this, there’s still a long way to go. An efficiency of 25 percent sounds impressive, but it’s not sufficient to help the blind see properly. The printed polymers must also be made much more sophisticated to really replicate eye cells. The other big issue is whether you can connect an artificial eye with the brain in such a way that someone can really see again. At the moment, the technology required to do so is still in its infancy.

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!

Image: University of Minnesota, McAlpine Group