Molecules work as a storage medium

Tailor-made powders can store information, and may well be more sustainable and stable than the current generation of hard disks. Researchers at Ghent University have shown that data can indeed be stored in simple molecules, but the process is anything but simple.

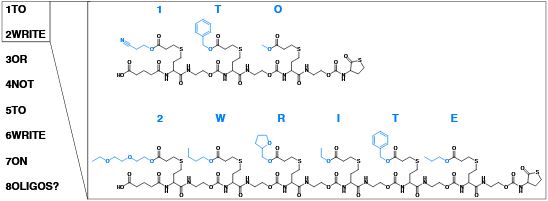

The Belgian scientists have successfully translated a sentence and a QR code into so-called oligomers, molecules consisting of a variety of monomers. They did so by hanging a different chemical group on each part of the molecular chain. This created an 'alphabet' that could subsequently be deciphered using a spectroscope and software.

STORAGE IN DNA

This represents the first step towards large-scale storage of data in molecules. Chemists and IT specialists share the hope that chemistry is the key to more sustainable, longer lasting storage media. Despite USB flash drives and hard disks apparently working very well, they do have their disadvantages. The data has a relatively short shelf life; a hard disk will lose much of the stored information after 100 years. Moreover, this storage medium requires the use of all kinds of scarce metals, and has a (relatively) limited storage capacity per square centimetre.

An alternative had therefore already been sought in the form of DNA: life's building block that can store a million times more data per surface area than silicon chips (read 'DNA as medium for data storage'). The disadvantage of DNA is that it is vulnerable and has a complicated structure. It also requires phosphorus, which is even more scarcely available than silicon. And that is why the Ghent-based scientists have now turned to molecules comprising simpler atoms: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen. All of them in plentiful supply on our planet.

SPECTROSCOPE

Only eight individual molecules were required for a simple sentence ('To write or not to write in oligos'). Each molecule consists of a number of parts (the number of letters in the word), and each part has a unique acrylate attached to it. The acrylates determine which part represents which letter.

The molecules were then passed through a spectroscope, and the results could be translated using software (that recognised which acrylate represented which letter). So a great deal of effort goes into storing a simple sentence in molecules. What's more, this method will not work in practice: there are not enough groups of acrylates to portray more extensive alphabets, such as the commonly used Unicode.

The research should therefore merely be seen as an example of data storage using molecules. The technology requires further refinement to render it more accessible. It is, however, proof that simple molecules can accommodate data, and that this is the future route for the massive storage of data.

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!

Image: Pixabay