Fleet of electric buses around Schiphol

Last week Connexxion presented a fleet of 100 electrically powered buses at Schiphol. The buses run in the Amstelland-Meerlanden region. It is the world's biggest ‘zero emissions’ project with the largest number of electric buses taking to the road in one go.

The fleet of buses was officially presented at Schiphol this week in the presence of Secretary of State Stientje van Veldhoven from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, representatives of all stakeholders, and the press. The attendees were given a tour of the airport in one of the buses, including a stop at a charging station.

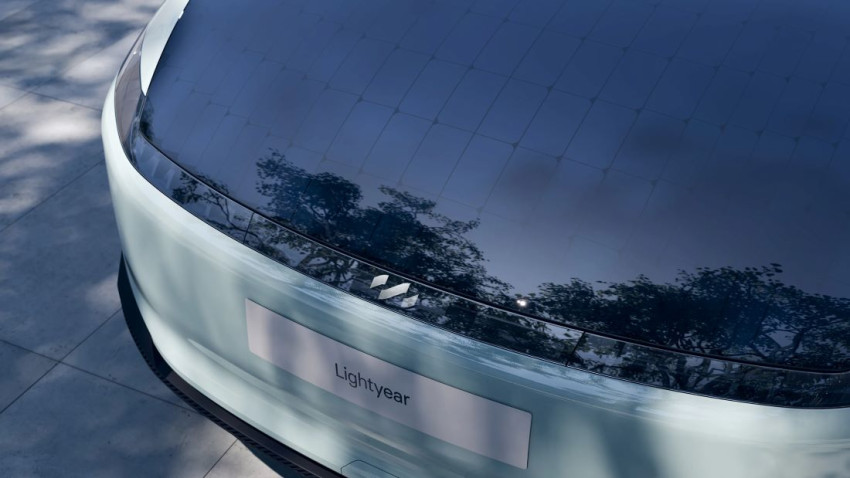

Of the 100 buses, 51 are stationed at Schiphol. These buses are silver. The other 49 R-net buses are red and are based in Amstelveen. The buses, manufactured by VDL, are all the same in technical terms, aside from the driver's cab, the nose and the interior. They are 18 m long and fitted with a harmonica in the middle. Empty they weigh 19 tons and have four battery packs on board that are integrated into the roof. The total capacity of the batteries is 170 kWh. The batteries feed an electric motor that transfers its power to the rear axle.

SCALE

Transport concern Connexxion already has vast experience in Eindhoven, where it has been running 43 electric buses in the city since 2016. But the bus company is taking it to the next level with this project. It's already a major challenge to launch 100 new buses at the same time, but it is even more complex to put 100 electric vehicles on the road to serve the area between Amsterdam, Amstelveen, Schiphol and Haarlem. In terms of buses, this is the busiest part of the Netherlands.

But what makes it so complex? Well for a start, the planning. Once a bus is on the road, it's on the road, but the new electric buses have to be charged between four and six times a day. A bus can run at least 80 km on a full charge. ‘The challenge was of course to ensure that the charging moments coincided as far as possible with the drivers’ breaks,’ says Frank Bleijlevens of Transdev, the parent company of the Dutch company Connexxion.

But infrastructure is also a challenge. To ensure the fleet of one hundred buses functions effectively - some routes run round the clock due to the hustle and bustle around Schiphol - fast-charge points have been fitted at four locations: three at different spots at Schiphol (P30, Schiphol-Noord and Cateringweg) and one in Amstelveen. At each of the locations, between four and eight buses can connect to the fast-charger simultaneously.

CHARGING PROCESS

The battery packs of the buses can be charged in two different ways. During the day using a fast-charger. The driver runs his bus to a fast-charge location and parks it precisely in the right slot, so that the bus's pantograph can be raised and locked into the contact hood (the roof-shaped object in the photo to the right). Charging then begins at a capacity of 450 kW, with the bus continuing on its way after twenty minutes or so. In Eindhoven, fast-charging still takes forty minutes. ‘This just shows how far technology has progressed in the last two years,’ says Bleijlevens.

NIGHT

’At night, when many of the buses are stationary, they are connected to the slow charger, which powers up the batteries at just 30 kW. Although this seems like a low capacity, it is enough to charge the batteries. During this process, the batteries are also balanced, i.e. the charge levels of the cells that make up the batteries are equalised. ‘In the morning, just before the bus timetable starts, the bus is 'woken up'. While it's still connected to the charging station, the bus and the batteries are preheated. This is necessary as cold batteries don’t work with fast-charge. If the materials in the battery are very cold, then they simply don’t accept large charging capacities,’ explains Connexxion's Zero Emission Manager, Bart Kraaijvanger.

DRIVING BEHAVIOUR

Compared with a diesel bus, electric buses have a number of benefits. First and foremost of course is that they don’t have any emissions. They are also quieter, which is positive for both passengers and local residents. The disadvantage is that they are considerably heavier than diesel buses, so they require a longer stopping distance in the event of an emergency stop.

The drivers have been trained to operate the new buses properly. By the steering wheel, for example, there is a handle that, if pulled, provides regenerative braking. That is to say that the energy from braking to a large degree flows back to the batteries. There is still a mechanical brake pedal in the bus, but the idea is to use electrical braking as much as possible.

A driver that we bumped into is very enthusiastic about how the bus drives. ‘It's incredibly stable on the road. It might be a little slower to get going, but I think that makes it even more comfortable for passengers.’ Due to the battery packs mounted on top of the bus, he takes it easy around corners. ‘Perish the thought that the bus flips onto its side while going round a corner.’

COST

A new electric bus costs about twice as much as a conventional diesel bus. In return, travellers and local residents enjoy cleaner air along the bus routes. For Connexxion, the investment is larger, but the electric buses are cheaper to maintain, are expected to last longer, and electrical power is cheaper per kilometre than diesel.

In recent weeks, Connexxion drivers have been carrying out a test programme on a number of the buses. This is not only to test the vehicles, both on the road and when charging, but is also to ensure drivers get used to the process. One step at a time, the first buses have already been added to the timetable. ‘We are now at 65 buses, but we must have completed the process by next Tuesday,’ says Eric Bavelaar of Connexxion.

In two years, Connexxion plans to add another 156 electric buses in the same region. It hopes to then be transporting 90% of the passengers using zero-emission buses.

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!

Opening photo: Connexxion