Bitcoin turns out to be very energy intensive

The cryptocurrency Bitcoin consumes around 200 kWh per transaction. That's enough to power 20 households a day. And some 300,000 transactions are verified daily. These figures come from Digiconomist, which is trying to establish the cryptocurrency's energy consumption.

The figures from Digiconomist speak for themselves. 200 kWh per Bitcoin transaction corresponds to 200 washes per day, or powering a Tesla Model S for some 1000 km. The total computer network that drives Bitcoin uses almost as much energy as Ecuador and more than Iceland. One thousandth of the world's energy consumption is used to power Bitcoin. These are astonishing amounts of energy. By comparison: a search on Google costs 0.0004 kWh. And according to a blog by ING economist Teunis Brosens, a Visa payment requires 0.01 kWh.

Embedded inefficiency

Bitcoin requires this much energy due to its algorithm, which runs constantly, generating (mining) each Bitcoin. 'And that is very inefficient. The algorithm ensures that Bitcoin is reliable, which is why it has to be very robust. And that requires a large number of people to execute the algorithm, and therefore use energy', explains Alex De Vries, founder of Digiconomist and consultant at PwC. 'The energy use is embedded in the 'proof-of-work algorithm'. But the rapid increase in the price of Bitcoin also plays a role.'

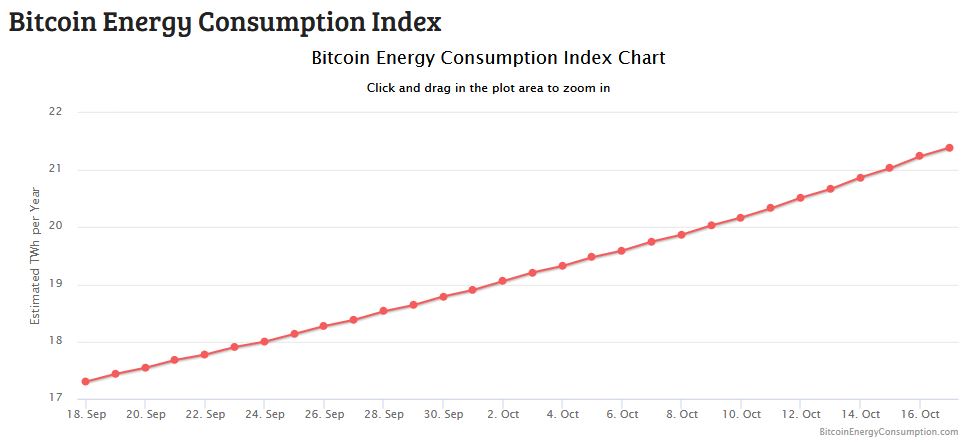

Bitcoin's energy demand has been gradually growing recently, partly due to the currency's explosive growth. In March, one Bitcoin was worth less than one thousand dollars, but is now touching six thousand. This ensures that more and more people want to obtain Bitcoin, and that costs a great deal of energy. As ING's Brosens put it: ‘It is very interesting, such a currency that avoids having to deal with banks or governments. But that system comes at a price, and that price is turning out to be considerable.'

Although the energy costs are given per transaction, that is actually a conversion. Far and away the largest amount of energy actually comes from the mining process. That involves networks of computers all obtaining the right to process a package of blockchain transactions. In exchange for processing, the mining community currently gains 12.5 Bitcoin every ten minutes, as well as a small transaction fee.

Estimate

The figures from Digiconomist are an estimate. It's impossible to say how much electricity the network uses precisely, as we're talking about thousands of computers and data centres. Alex de Vries, founder of Digiconomist, makes this estimate using the turnover of miners and the presumed energy prices. ‘We know that an estimated sixty percent of the turnover of miners disappears in energy costs. Other costs, such as personnel or equipment, are nothing in comparison, so you can assume that most of it is energy. We then assumed a conservative estimate of electricity prices of around five eurocent per kilowatt hour. By then dividing sixty percent of the turnover of all miners by the kWh price, you arrive at consumption levels.'

Is there an alternative?

De Vries thinks that Bitcoin energy demand is unlikely to fall any time soon. ‘Even measures built into the system, such as the periodic halving of the reward for mining, are not effective if the currency more than doubles in value.' One possible solution, according to de Vries: modifying the algorithm. 'There is a new method for executing the 'random draw', which determines who may process a transaction and gain Bitcoin. Not via an energy-intensive algorithm, but simply a random choice by computers in a network. Such a 'proof-of-stake algorithm' only requires a computer to be switched on, rather than being hard at work. This means it uses 0.01 % of the energy of the Bitcoin algorithm.'

The second most popular cryptocurrency, Ethereum, is soon due to switch to such a system, according to De Vries. 'The community must be absolutely certain that it works properly and is secure enough to be viable.' De Vries also emphasized that there is a heated discussion as to whether or not proof-of-stake can work as well as the method currently used by Bitcoin. Brosens also sees a more fundamental objection: 'Proof-of-stake’ requires a sort of collateral. And that means that only people with money or other means can be miners. It seems to me that this runs counter to the egalitarian principle upon which Bitcoin was developed. However, mining is already a game often played by the wealthy who can afford to rent data centres.' So we will have to wait and see whether Bitcoin fanatics are happy with a switch to such a system. It would at least be a blessing for the environment.

Did you like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Image: MichaelWuench