Subsidence is a serious problem

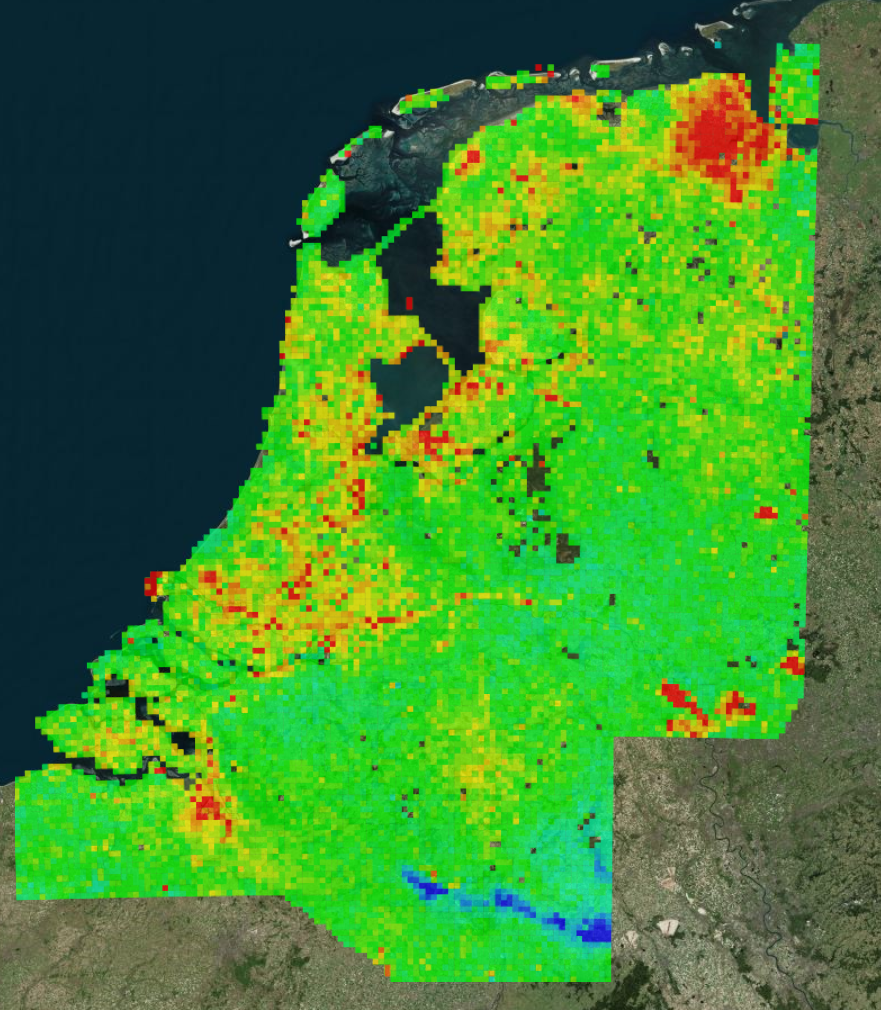

Subsidence in peat and clay soils specifically in the western part of the Netherlands is developing faster than had previously been assumed.

This is illustrated in the new Subsidence Map of the Netherlands, presented this week by the Netherlands Centre for Geodesy and Geo-Informatics (NCG).

Especially 'shallow' subsidence turns out to be far greater than had been anticipated until now, and occurs particularly in peat and clay soils. The drought this past summer only accelerated this process, causing cracks to appear in some homes.

The shallow subsidence has been determined for the first time using satellite and gravitational measurements, states the press release from Delft University of Technology, where the map was compiled.

Until now, the soil map has been drawn up using manual gauging: Rijkswaterstaat sent out surveyors to carry out roadside measurements with their instruments. The new, interactive map, drawn up under the direction of professor in Geodesy and Satellite Earth Observation Ramon Hanssen (NCG / Delft University of Technology), uses satellite radars, GPS and gravitational measurements. The new map is thus not based on a ‘paltry’ 35 thousand data points, but on no less than 31 million. Another major difference is that surveyors only carry out new measurements once every ten years, while the satellites do this every single day.

Anyone may consult the map on the website bodemdalingskaart.nl, and it is kept up-to-date on a daily basis with new satellite measurements.

The map also shows where oil and gas is being extracted. This should also clarify whether or not reduced natural gas extraction in Groningen will bring a halt to the subsidence there.

Climate change

According to the map's compilers, climate change is a major cause of the increased subsidence. This is especially true for the low-lying peat soils in Holland and the northern provinces. The combination of dewatering by agriculture and the dry summer has resulted in extremely low groundwater levels. Drained peat soils 'burn' with oxygen. This peat oxidation process not only accelerates subsidence, but also releases more CO2. At some spots in the west of the Netherlands, the ground is subsiding faster than in the natural-gas extraction areas in Groningen, say the researchers. Moreover, the subsidence is going faster than the sea-level rise, at up to half a centimetre per year in some locations. If no measures are taken, then by 2050 the soil will be as much as half a metre lower than today.

The extremely low groundwater levels also have consequences for older buildings and dwellings built on wooden piles: when they dry out, they rot. But nature reserves are also affected: they are drying out as the water is flowing to lower-lying and desiccating areas of peat soils.

According to Hanssen, we are talking about a serious problem. ‘If subsidence continues at this pace, it could mean the end of the characteristic Dutch landscape with meadows, cows and windmills, or enormous damage to historic town centres,’ he says in a press release from Delft University of Technology. The damage could amount to as much as 22 billion euros.

Irreversible

Peat oxidation is an irreversible process. Water authorities can only prevent the subsidence continuing at the current rate by maintaining water levels more consistently and anticipating periods of drought, suggests Hanssen.

Two years ago, the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency had already warned about the high costs of subsidence in peaty areas (read: 'Subsidence means high costs').

Nearly 10% of the territory of the Netherlands is peaty soil. Earlier this year, a group of experts launched an initiative to prevent the Frisian peaty soils from disappearing completely over the coming decades (read: 'The impending demise of the Frisian fens'). They argue for flooding a portion of the fens.

Opening photo: Platform Slappe Bodem/Vincent Basler