Lithium and cobalt shortage by 2050

The arrival of electric cars has quickly increased the demand for lithium and cobalt. If no action is taken, they will be in short supply by 2050, German researchers have warned. Moreover, these materials are mainly mined in politically unstable countries. The solution to these problems lies in (better) recycling of batteries and development of new types of batteries based on other materials.

That is the conclusion of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and the Helmholtz Institute Ulm (HIU) in the journal Nature Reviews Materials.

Encouraged by automobile manufacturer Tesla and possibly helped along by the recent diesel scandals, electric driving is now taking off. Nearly all manufacturers have launched a fully electric model or have plans to do so in the years to come. Even buses are becoming electric, with Dutch cities Utrecht and Eindhoven already having dozens driving around, and it was recently announced that Amsterdam Airport Schiphol will soon be deploying a hundred.

Downside

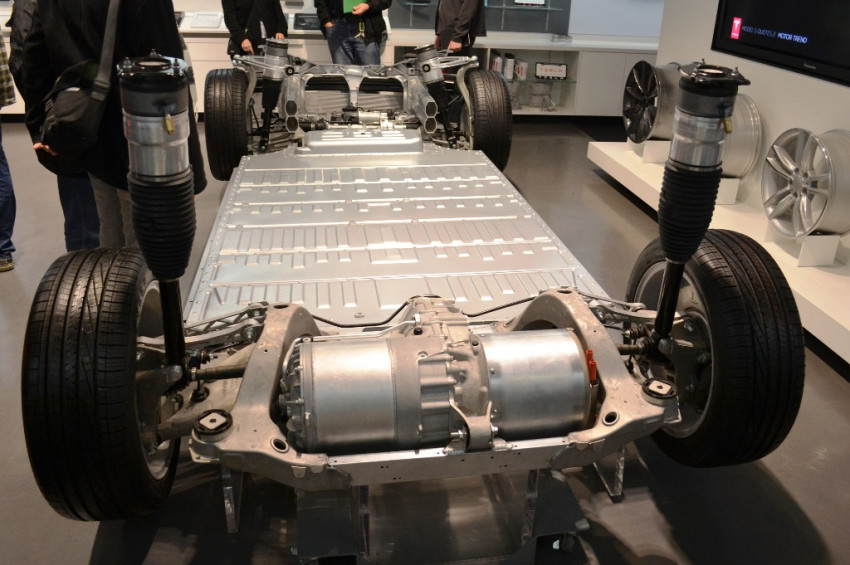

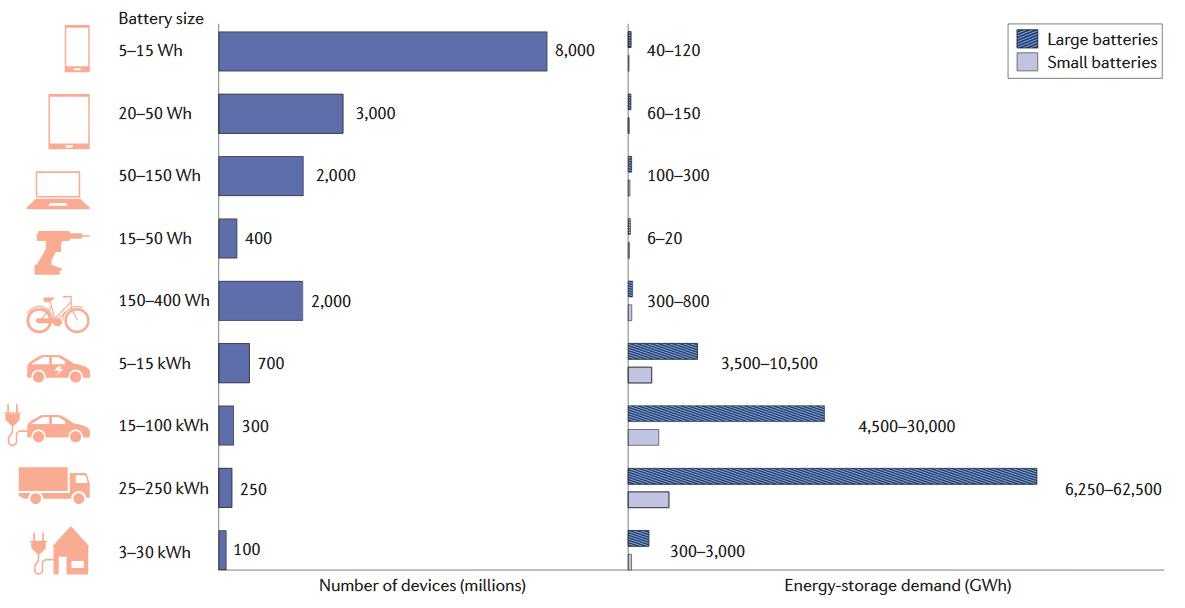

This is all excellent news for air quality, as these vehicles have no direct emissions (aside from how the electricity was generated in the first place). There is, however, another side to the electric transport boom. The vehicles all have large battery packs on board, made partially from scarce materials. The breakthrough in electric transport will therefore significantly increase demand for these rare materials, as shown in the figure below. The researchers predict that 700 million fully electric cars will be produced, along with 250 million electric trucks and 100 million home battery packs, such as the Tesla Powerwall, between 2016 and 2050.

Cobalt

Let us begin with cobalt. This is the material required for lithium-ion battery cathodes, but it is also scarce and toxic, according to the Germans. Their scenario predicts that, by 2050, the demand for this metal will be double the known reserves currently in the ground. The price development is equally sombre: cobalt has already more than doubled in price from 2016 to 2017. Moreover, children are all too often deployed in strenuous and risky mining operations in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Lithium

And then lithium, of which around 63 kg is needed for each Tesla car battery with 70 kWh energy volume. The lithium reserves are somewhat more plentiful, though production levels will need to increase tenfold in order to meet the forecast demand. A complicating factor in this case is that the (known) lithium resources in the ground are mainly in three countries: Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. Due to these countries lacking any lengthy tradition of political stability, the researchers are somewhat concerned about future availability of the material. Concentration in a limited number of countries is never favourable. 'It is therefore indispensable to expand the research activities towards alternative battery technologies in order to decrease these risks and reduce the pressure on cobalt and lithium reserves,' explains fellow lead researcher Daniel Buchholz of the Helmholtz Institute Ulm in a press release.

Sodium battery

In their paper, the researchers concentrate on whether lithium can be replaced by sodium, a material which is in much more plentiful supply on earth and which is less toxic. A cost analysis shows that a sodium-ion battery is not directly cheaper than a lithium-ion version. Once lithium becomes scarce however, the price will increase to such a degree that the sodium-based battery gains attractiveness. It must be noted though that the technical performance of the sodium version cannot yet match that of its lithium peer. So enough research work ahead then.

Another way of easing the pressure on the scarce materials is to reclaim them from discarded batteries and devices. Insufficient attention has been given to this option so far, as is the case throughout the automobile industry. There are plenty of ideas on how to achieve this, though there are also technological challenges.

Opening image: Undercarriage of a Tesla Model S car, with the large battery pack in place. Photo: Oleg Alexandrov