Densified wood performs like steel

Engineers from American universities have devised a new method for densifying wood so the material matches the mechanical properties of steel.

Densifying wood considerably enhances its mechanical properties. One company doing this is the Dutch Platowood company, which heats wood harvested from quickly growing trees to around 180 °C before compressing it, giving the quickly growing wood the same properties as tropical hardwood.

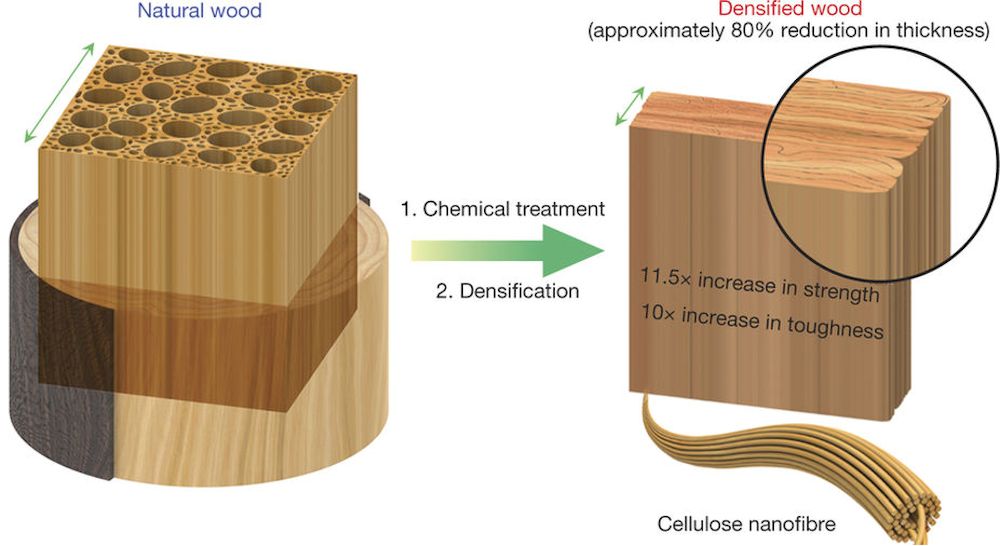

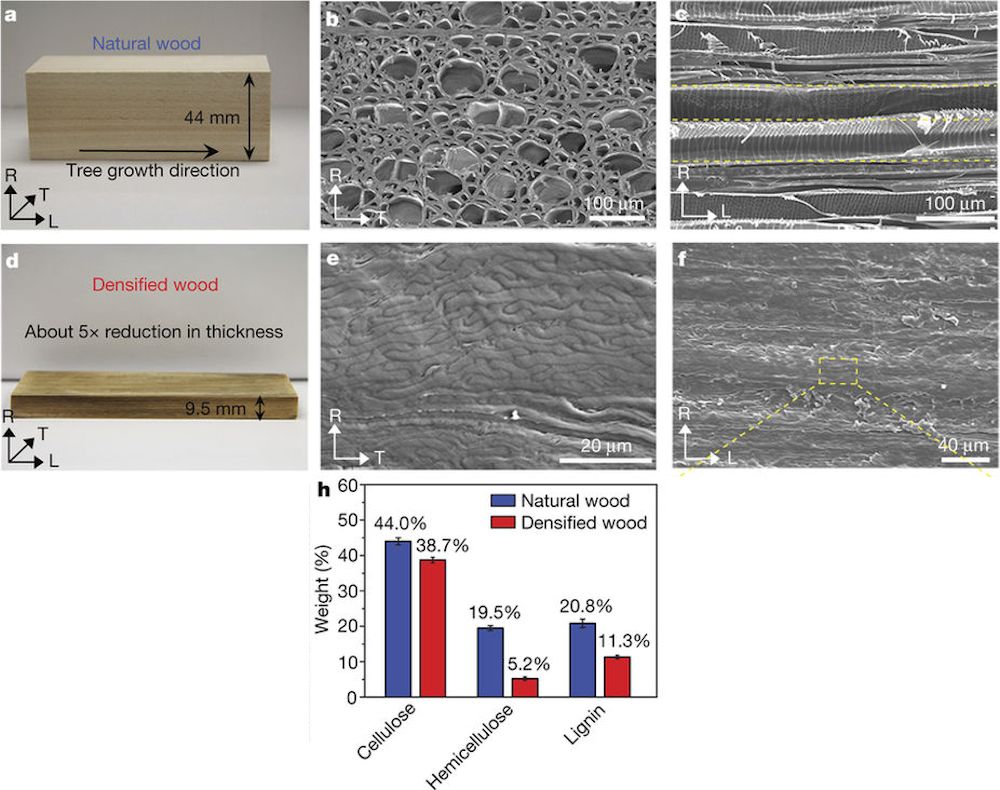

Engineers from the materials faculties of various American universities have gone one step further. They begin by treating the wood in a bath of caustic soda and sodium sulphite, an aggressive cocktail which dissolves and largely removes the harder components of the wood (lignin and hemicellulose). The leached wood is then compressed at 100 °C perpendicular to the growth direction, rendering the wood nearly five times thinner.

All air is removed from the wood

The chemically treated wood has much better performance properties than simply densified wood. Removal of the hard components results in all of the capillaries in the wood being compressed during the densification process. This cannot be achieved without the chemical treatment. And so the cell walls form an interwoven structure, while the cellulose fibres retain the structure of untreated wood.

This results in a material which performs well for virtually all mechanical properties: tensile strength, toughness, scratch resistance, and flexibility all score better than normal wood by a factor of 6 to 12. The densified wood therefore equals and even outperforms the properties of construction materials such as synthetics and steel. This has been proven in various tests, including even the impact of a bullet on the wood.

Environmental impact

In their article on densification of wood in Nature magazine, the engineers make no mention of what happens to the alkaline bath used to dissolve the hard components of the wood, or the energy required to produce the densified wood. Nor do they compare this with the 'footprint' of steel production, for example.

That aside, the method facilitates the creation of beautiful construction materials from quickly growing species of wood, with many applications.

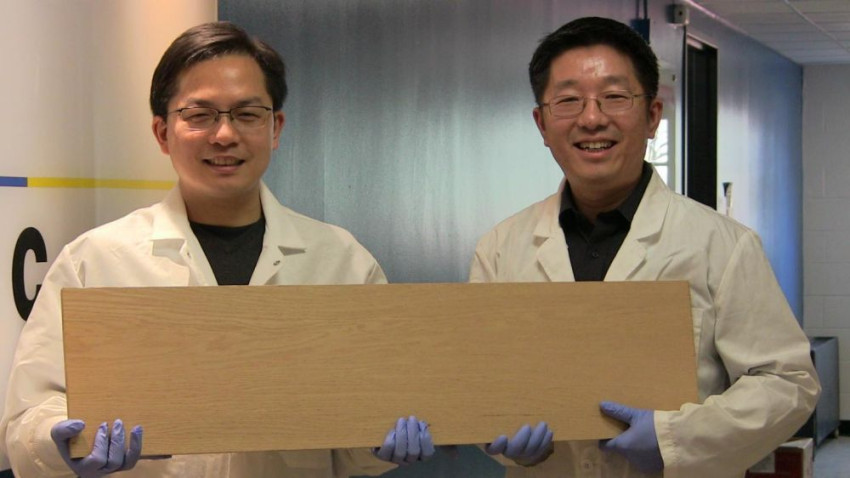

Opening photo: the engineers Liangbing Hu, left and Teng Li, of the University of Maryland, College Park with a sheet of their processed wood. Photos courtesy of University of Maryland

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!