Making Amsterdam more sustainable

Making Amsterdam sustainable by 2050 means that the city must connect 100 homes a day to the existing heating main and fit 325 solar panels to roofs. That's the revelation recently presented in the Energy Transition Roadmap.

'Sustainable by 2050!' That's a slogan you'll hear from many political parties right now, now that the local Dutch elections are looming upon us. It's easy to say, but what does it really mean in practice?

This has been thoroughly researched for Amsterdam, and the result – the Amsterdam Energy Transition Roadmap – was presented on 15 March. The Roadmap itself is not yet available.

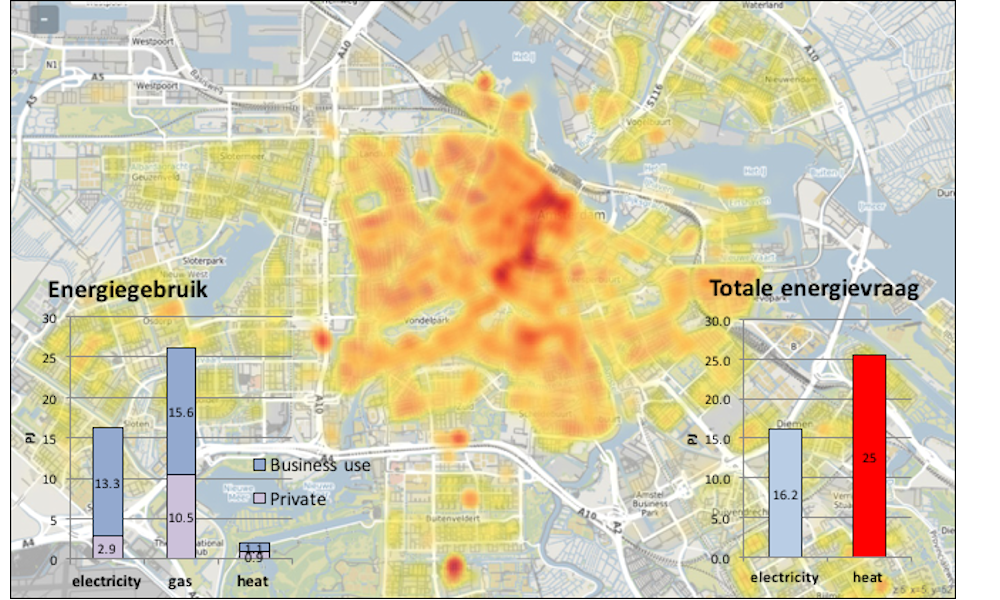

The study was limited to the demand for heat and the electricity consumption of homes and other buildings, so is not concerned with transport, for instance. It also considered what was necessary, and what the potential is for sustainable sources or energy savings.

Not surprisingly, the older residential areas have the highest energy usage, especially in the city centre. And in homes it's the heating in particular that demands the most energy.

Insulation helps most

The best solution for reducing this demand for heat is properly insulating homes. This might be to the standard of the extreme A+++ energy label, but could also include that of the less extensive B label. ‘In the Westelijke Tuinsteden districts of Amsterdam, for instance, you can achieve a great deal with insulation, but it'll be a lot more difficult in the old canal-side homes,’ says Professor Andy van den Dobbelsteen of Delft University of Technology, who presented the Roadmap.

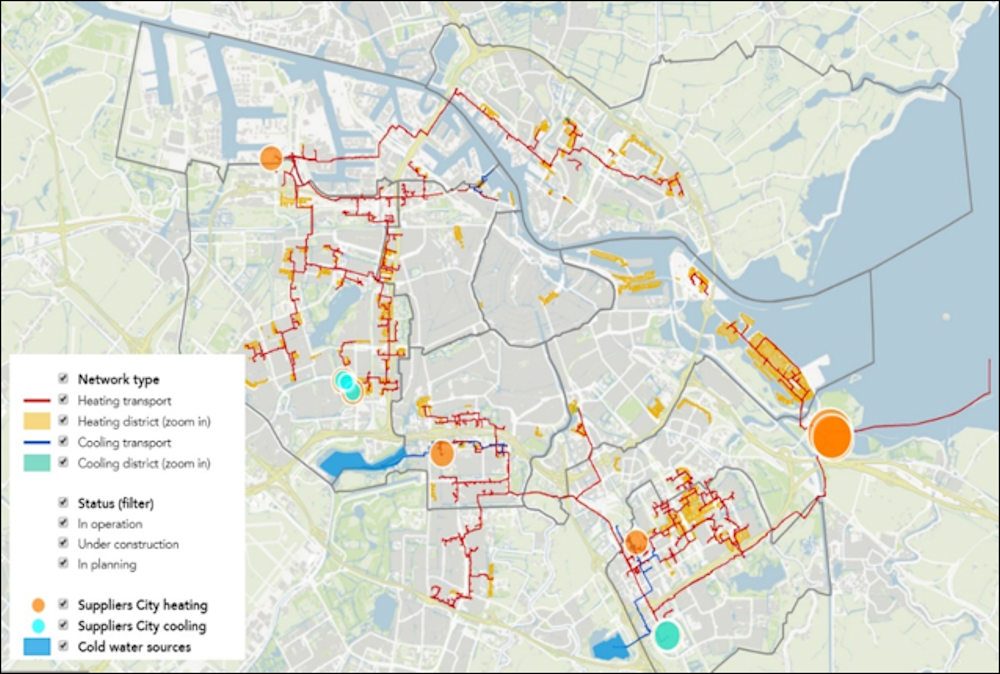

Built around WWII, a sustainable alternative for heating homes in the Westelijke Tuinsteden districts could be ground-source heat pumps. But for the 19th century suburbs, and even more so for the older city centre, options are limited by a lack of space and monument conservation rules. ‘Connection to the heating main is an alternative here.’ Green gas, produced for example by fermenting organic waste, is also an option, but the possibilities for doing this in Amsterdam itself are limited.

Low temperature heating network

There is a clear synergy to be gained from both insulating homes and connecting them to the heating main. ‘If homes are well insulated, you can use a low-temperature heating main of around 35°C. The potential availability of this in future is many times greater than the high-temperature heat of some 80°C that the existing heating main provides,’ says Van den Dobbelsteen. The current heating main is now supplied by the city's waste incinerator and a gas-fired power station in Diemen. ‘We want to avoid both those sources in future.’ Incidentally, there is a study planned in Amsterdam to investigate the possibilities of a geothermal heat supply for high-temperature heat.

The existing high-temperature heating main in Amsterdam currently makes a large circuit around the old city. ‘So it must first be expanded to include the old city before it forms a proper alternative to natural gas.’ The Roadmap puts this into figures: up to 2030, some 26,000 new connections to the existing heating main need to be made annually, equivalent to 78 km of heating main a year. What's more, every year 15,000 homes need to be better insulated and connected to a low-temperature heating main, while at the same time 13,000 homes a year need to be made energy neutral.’ All things considered, this means tackling 54,000 dwellings every year!

Heritage pv

Electricity consumption will increase heading towards 2050, partly due to the use of ground-source heat pumps. Some of that power is delivered by roof-mounted solar panels. Some 140,000 m2 will have to be fitted annually up to 2030, or 325 panels per working day. ‘And that requires permanently employing 48 fitters.’ With the townscape and monument conservation in mind, there is very little scope for fitting the usual panels within the ring of canals that surround the historic centre of the city. ‘Amsterdam could be a launching customer for "Heritage PV", or solar panels integrated into roofing tiles that are almost identical to the existing tiles.’

Further to that, the Roadmap wants to significantly increase the number of wind turbines in the port area, with five new units of 4 MW each year. But given the intensity of energy consumption, the city cannot operate without importing green energy, for instance from North Sea wind farms.

The Roadmap is one of the first that suggests how a city can become more sustainable based on its existing energy usage. So this ambitious promise leads to the conclusion that there is a great deal left to do.

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!