Nuclear energy – it’s not that simple

Can nuclear power stations help us make the transition to CO2-free energy supplies? A majority comprising the VVD, CDA, PVV, SGP and Forum voor Democratie political parties in the Dutch parliament believes it can. How did this ‘U-turn’ come about? And is it really that simple?

It’s not yet clear what triggered the renewed interest in nuclear energy. Has a magical power station suddenly materialised, which performs fantastically for a modest price? Apparently not. In fact, quite the opposite, but more on than later.

IPCC sounds the alarm

A more obvious reason for the renewed popularity of nuclear energy among politicians is the recent IPCC report that insists on immediate action if we want to keep global warming below 1.5°C. In that light, it seems logical to take up arms quickly on every front, including nuclear energy. The same readiness for action should also apply to reducing industrial emissions and initiating a large-scale insulation programme for old housing stock. However, do we see the same call to arms here after publication of the IPCC report? We’ll have to wait and see what happens in the next month, when the climate agreements are detailed.

Only the liberal party VVD is consistent

Hearing politicians argue the case for nuclear energy was unexpected, in any case, because you need a microscope to find any mention of it in the election manifestos published last year in the Netherlands. Only the liberal party VVD has maintained a consistent position: its manifesto states that nuclear energy must remain an option.

The Christian party SGP will only accept new nuclear power stations 'that are absolutely safe, and do not generate long-term waste'. The term nuclear energy cannot be found anywhere in the manifestos of the parties CDA, PVV or Forum voor Democratie. All the other political parties explicitly opposed new nuclear power stations.

No magic power station

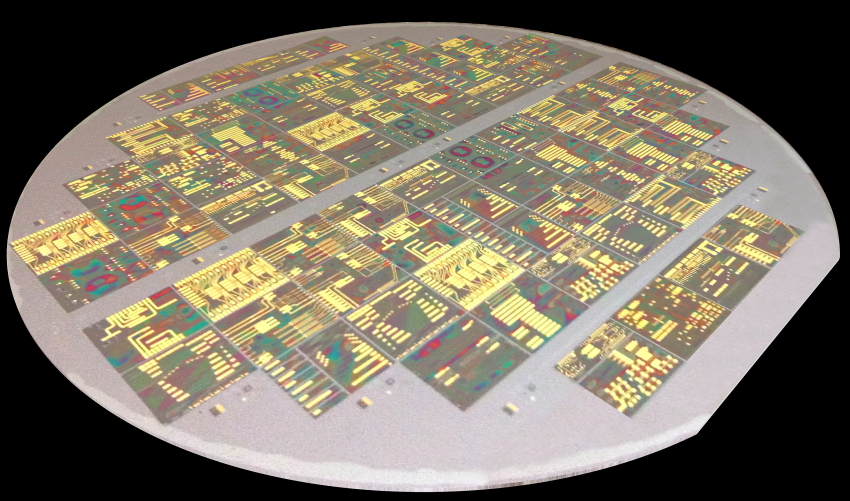

Nuclear power is now firmly back on the agenda. It emits no CO2 and nuclear fission requires only small amounts of uranium to generate a lot of electricity. What’s more, nuclear energy isn’t dependent on the vagaries of the weather.

Can we use the existing type of power stations? They need a lot of safety measures, and land us with a long-lasting legacy: from demolishing obsolete power stations to nuclear waste. Should we take an alternative route, and invest in developing the thorium reactor, where the waste issue is less acute but the technology far from ready?

If something goes wrong at a nuclear power station, the consequences are devastating. Not so much in terms of number of victims, fortunately, but mainly because of the ensuing disruption and the tens of billions of euros needed to limit radioactive pollution. OK, but you have to weigh that risk against the consequences of climate change.

Are costs no longer relevant?

What does now play a major role in the discussion about nuclear energy is the cost, because that’s where it’s bad news all the way. Even though you’d expect that using existing technology would mean a gradual reduction in costs, the very opposite happens with nuclear energy, and in no small terms. The costs of the new nuclear power stations currently being built in Finland, France and the United States have rocketed to three times the original forecasts. The construction of a large 1,600 MW power station will soon cost 11 billion euros in these countries.

There was once a time when nuclear power promised to be the cheapest way to supply energy, but those days are long gone. That makes it all the more strange to see parties like the VVD and CDA fretting about costs to the citizen during the negotiations about a new climate agreement last summer, but apparently unconcerned with this aspect when defending nuclear energy.

You could argue that if we all make a major commitment to nuclear energy, those costs will automatically go down. However, that major commitment was called the renaissance of nuclear energy ten years ago, when there were plans in the US to build ten new nuclear power stations. Experience has taught us that financial constraints have made it barely possible to complete even two. Apparently, it’s very difficult to reach the point where economies of scale kick in.

American university MIT recently published a stinging study on these costs: if nuclear energy wants to play a role in a low-carbon energy system, its costs will have to be reduced significantly. Nuclear energy will gradually fizzle out if this can’t be done, according to one of the compilers of the study.

It’s all very well advocating nuclear energy, but you have to take the whole deal on board. Otherwise, it’s nothing more than a lot of hot air.

Further reading

Nuclear energy is too expensive

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!

Opening photo: on the right, the new nuclear power station in Flamanville, France, where costs have reached 10.9 billion euros compared to the original 3.3 billion budget.