The Netherlands has a chance to produce electrolysers

The Netherlands should focus on the development and production of electrolysers that convert renewable energy into green hydrogen. AkzoNobel's Joost Sandberg argued this point during a meeting entitled ‘Our energy future’ of the Royal Netherlands Society of Engineers (KIVI).

Sandberg submitted his proposal during a presentation about the initiative by AkzoNobel Speciality Chemicals and Gasunie to convert renewable electricity into hydrogen using electrolysis. With a capacity of 20 MW, this factory will immediately be the largest in Europe.

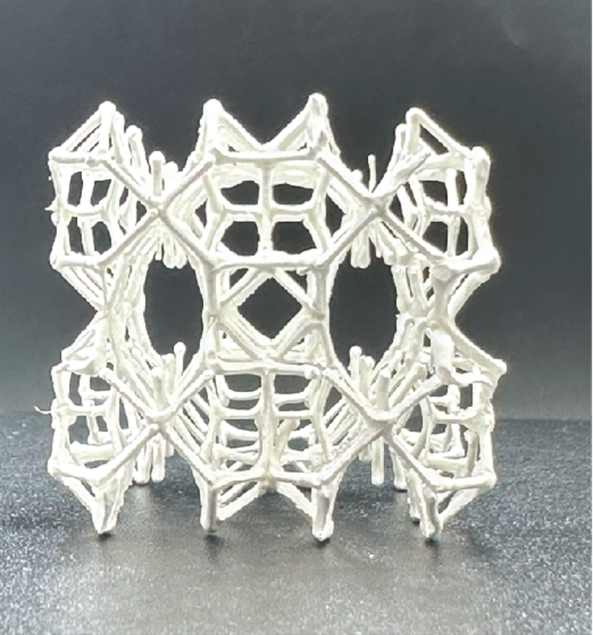

One bottleneck is finding water electrolysers of a large enough scale. These use electricity to strip water into oxygen and hydrogen. ‘There are of course companies that supply these, but it's not yet what you might call a ‘booming business’. And that is understandable, as it is currently cheaper to generate hydrogen from natural gas.’

Plenty of demand

With an eye to switching to a low-CO2 energy supply, green hydrogen will play a much greater role. The KIVI energy plan – the reason for holding the meeting – discusses hydrogen production with a capacity of dozens of gigawatts, both for industrial processes, heavy transport and for a buffer for periods in which sun and wind are delivering very little power. The industry in the Netherlands currently already uses a lot of hydrogen, accounting for 7 GW demand for hydrogen. ‘So there's no shortage of demand.’

For a sustainable future, hydrogen production from natural gas will have to stop at some point. ‘This will create huge demand for green hydrogen, and we'll be needing electrolysers for that.’ According to Sandberg, the Netherlands possesses the competencies to produce electrolysers. ‘Membranes, electrodes, electronics, process technology, research capacity – we have the necessary knowledge and expertise. But we need to deploy them in a more targeted way to kick off the production of electrolysers.’

Green hydrogen manifest

Sandberg’s argument corresponds with a manifest published by the Waterstof Coalitie of companies, environmental organisations and energy concerns. They are demanding that the government set out a roadmap towards large-scale production of green hydrogen, starting at 20 MW in 2018 to 3/4 GW by 2030. As with offshore wind energy, the government will have to act as guarantor in funding the unprofitable top layer (for now, green hydrogen will be more expensive than hydrogen from natural gas), with companies being challenged via tenders to produce the hydrogen as cheaply as possible. This will have to go hand in hand with innovation programmes aimed at the production, transport and application of hydrogen. According to the compilers of the manifest, a cost reduction of 65% is possible by 2030. The companies also promise that they will use green hydrogen.

Hydrogen train

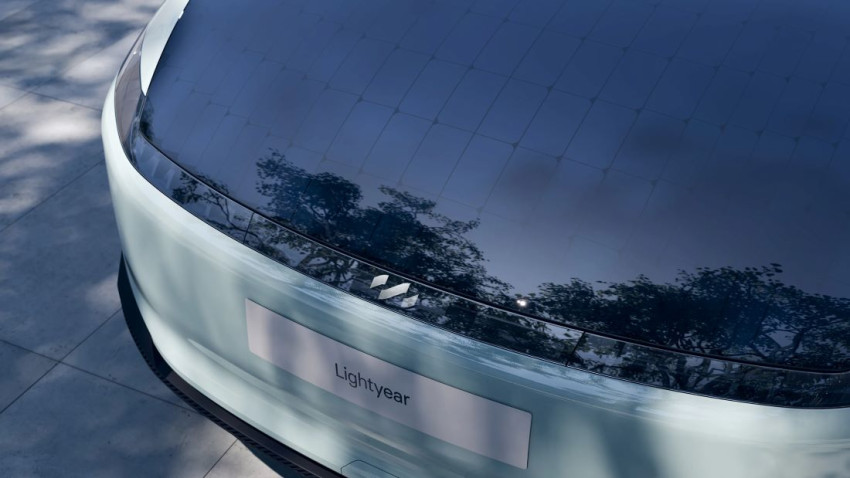

It was also announced that a trial will be initiated on the Groningen-Leeuwarden line using a hydrogen train. This line currently uses a diesel-powered train. The train will be produced by Alstom, that already has a similar train running in Germany. Electrification of the line is significantly more expensive than using green hydrogen.

Keep the offsetting scheme

Marjan Minnesma, CEO of Urgenda and one of the speakers yesterday at the KIVI energy meeting, placed major emphasis on keeping the offsetting scheme. This scheme allows people who deliver solar energy to the power grid to then take the same amount of power back for free. The current cabinet is planning to repeal this scheme and replace it with a different but less favourable one. ‘Our practical experience with making homes more sustainable suggests that the offsetting scheme motivates people to participate. This scheme makes it financially more attractive to place solar panels, also for lower-income individuals. So keep it going to ensure that homes can be made more sustainable at a faster pace.’ According to Minnesma, the amount involved shouldn't be a problem in relation to the total sum required for the energy transition.

Her argument for the offsetting scheme also reflects her call to start by plucking the low-hanging fruit when making homes more sustainable. ‘That's not specifically with the large complexes of the housing corporations, but with detached, semi-detached and terraced houses. So prioritise those over apartment blocks, as the latter already use a lot less energy.’

If you found this article interesting, subscribe for free to our weekly newsletter!